Murphy's Law states: "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong." This is especially true and especially painful when there is an audience involved.

|

In a recent blog post, Pat Ahaesy used three scenarios to illustrate the idea that a lot of production disasters can be avoided through good communication. In a recent blog post, Pat Ahaesy used three scenarios to illustrate the idea that a lot of production disasters can be avoided through good communication.

Things that sound so simple, but done on the fly due to poor communication can be costly. Things that sound so simple, and done without communicating in advance to your producer can either not happen as you envision or not happen at all

Some examples of “simple” that could be a disaster, but can be avoided with good communication:

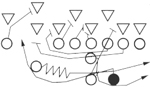

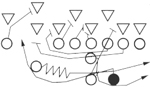

- Planner wants stage set for 4 person panel with all panelists center stage on high stools and moderator at a lectern, stage right. During chats with another planner, the decision is for the panelists to be seated on two couches on a diagonal. They will omit the lectern and have moderator seated on a chair. The lighting designer and your producer haven’t been told of this change. Of course, the different seating needs to be sourced quickly and the lighting designer has to re-focus his lighting. Much stress and potential errors could occur.

I think we’d all agree completely that good, early communication is crucial to avoid disaster. Why it’s so difficult?

Ahaesy attributes it to budget concerns:

Sometimes management and/or procurement feel that contracting production early in the planning stages can cost more money.

I’m not sure that there’s really that much thought being put into. My guess is that a profound lack of communication is often caused by what I like to think of as the Magic Button Assumption. Professionals that inhabit one area of expertise often assume professionals that inhabit another have a magic button that allows them to make anything that needs to happen happen with no fuss, no muss and no preparation or planning. The funny part is that any they would find any suggestion that they possess a magic button of their own too ridiculous for words.

The reasons a client might be making this assumption are many and it might be interesting to talk about them in future posts. The most obvious is that clients often don’t really understand what it is we do and how the tools we use work.

The more I think about it the more it seems that this phenomenon needs to be part The Principles. It also needs to be explored through the discussion of real life examples. I’ll be tracking some down from my own experience and I would really appreciate it of you would be willing to share your own stories. Feel free to put them in a comment to this post or let me know if you would like to do a guest post.

Or maybe it’s so mundane and ubiquitous it’s not worth discussing at all. One way or the other please weigh in and let us know what you think.

“When you have plans, roles, and responsibilities in place, you will reap the rewards many times over if a disaster actually occurs. Rather than scrambling about to figure out who should do what, you can calmly and effectively monitor what is happening. If key personnel are away, you can adjust the roles and responsibilities as needed. You can decide what should be communicated, and when, to the organization.” “When you have plans, roles, and responsibilities in place, you will reap the rewards many times over if a disaster actually occurs. Rather than scrambling about to figure out who should do what, you can calmly and effectively monitor what is happening. If key personnel are away, you can adjust the roles and responsibilities as needed. You can decide what should be communicated, and when, to the organization.”

(“Intranet Librarian,” by Darlene Fichter, Online, March/April 2005, p. 51-53. via http://nnlm.gov/ep/2006/10/27/disaster-planning-quotation/)

As you may remember from an earlier post, my first real job was at a McDonald’s. Started the day after I turned sixteen. You might also remember that I got into some trouble because I didn’t deal with burning my fingers in way that had approval from corporate headquarters. They were funny about stuff like that. As you may remember from an earlier post, my first real job was at a McDonald’s. Started the day after I turned sixteen. You might also remember that I got into some trouble because I didn’t deal with burning my fingers in way that had approval from corporate headquarters. They were funny about stuff like that.

They were also very, very specific about how every product that crossed the greasy steel counter — the fries, the milkshake, the secretive big mac, even the most humble hamburger –Â came into being.

It began with the burger flipper’s tools-of-the-trade. They were to be arranged just so. You always put the spatula in one specific place. The bins with the pickles had to be all the way to the left with bin holding the now reconstituted. formally dehydrated onions were always next. The strange thumb-controlled funnel thingy that deposited exactly the right amount of ketchup was always in exactly in the same place, in it’s holder, on the end of the counter. The mustard funnel thingy was always to its right. At least that’s the way they did it back in the eighties. It began with the burger flipper’s tools-of-the-trade. They were to be arranged just so. You always put the spatula in one specific place. The bins with the pickles had to be all the way to the left with bin holding the now reconstituted. formally dehydrated onions were always next. The strange thumb-controlled funnel thingy that deposited exactly the right amount of ketchup was always in exactly in the same place, in it’s holder, on the end of the counter. The mustard funnel thingy was always to its right. At least that’s the way they did it back in the eighties.

In fact, they were even more picky, if you can believe it, with the way you actually put the burgers together. There were videos for God’s sake. Written tests.

The one part of the intricate construction process that’s stuck with me all these years is the importance of putting the mustard on the bun before the ketchup. If I remember correctly, they told us that this kept the mustard from coming into contact with the meat which burned it chemically and gave it a funny taste. Who knew?

And pickle slide placement, don’t get me started on pickle slice placement.

All this formality might seem silly, but being forced to be highly regimented in something as simple as making a hamburger was actually very useful. It was great when you were suddenly in the middle of a huge Saturday afternoon rush and everything was exactly where it was supposed to be and it almost became unnecessary to think about what you had to do next. As things got busier, and the shift ground on and on, and the brain got more tired, it was possible to enter a zone where the entire process flowed effortlessly out of a combination of muscle memory and mental habit.

What the heck does this have to do with presenting?

In the grand scheme of things, providing a good presentation experience is almost always more important than providing a good hamburger. So if someone is willing to put all that time, effort and thought into the process of serving up a Whopper, shouldn’t you be willing to apply a little additional rigor to thinking about how you go about preparing to do what you need to do as a presenter (or as someone helping a presenter)?

Are there parts of your preparation process that you haven’t given any thought to at all?

There’s a crucial file on your laptop, the PowerPoint for Monday’s presentation. Do you know exactly where it is? Is it on your desktop? If it in a folder, which one? Can you instantly and easily distinguish it from any other file that might be in the same folder? Are you absolutely certain you have the most current version?

You’re given a couple hours at most to set up. And the room layout doesn’t come close to matching the diagram they emailed (you didn’t do a site visit?) and you need to put the short throw lens into the projector. Quickly. Do you know exactly which case it’s in? Is it still out in the truck? You’re probably going to need a screw driver. Where is it?

Do you have a documented (or at least habitual) setup routine that will help save your butt when everything else is going completely to hell in a hand basket? Like that time. You remember. The snowstorm? The delayed flight? Getting to the hotel two hours before call time? Stiff necked, sleep deprived and brain dead but the show still had to go on.

Have a plan, have a routine, know how to find exactly what you need exactly when you need to find it. Or be prepared to find yourself going from being under fire to working the deep fryer.

|

In a recent blog post, Pat Ahaesy used three scenarios to illustrate the idea that a lot of production disasters can be avoided through good communication.

In a recent blog post, Pat Ahaesy used three scenarios to illustrate the idea that a lot of production disasters can be avoided through good communication. “When you have plans, roles, and responsibilities in place, you will reap the rewards many times over if a disaster actually occurs. Rather than scrambling about to figure out who should do what, you can calmly and effectively monitor what is happening. If key personnel are away, you can adjust the roles and responsibilities as needed. You can decide what should be communicated, and when, to the organization.”

“When you have plans, roles, and responsibilities in place, you will reap the rewards many times over if a disaster actually occurs. Rather than scrambling about to figure out who should do what, you can calmly and effectively monitor what is happening. If key personnel are away, you can adjust the roles and responsibilities as needed. You can decide what should be communicated, and when, to the organization.” As you may remember from

As you may remember from  It began with the burger flipper’s tools-of-the-trade. They were to be arranged just so. You always put the spatula in one specific place. The bins with the pickles had to be all the way to the left with bin holding the now reconstituted. formally dehydrated onions were always next. The strange thumb-controlled funnel thingy that deposited exactly the right amount of ketchup was always in exactly in the same place, in it’s holder, on the end of the counter. The mustard funnel thingy was always to its right. At least that’s the way they did it back in the eighties.

It began with the burger flipper’s tools-of-the-trade. They were to be arranged just so. You always put the spatula in one specific place. The bins with the pickles had to be all the way to the left with bin holding the now reconstituted. formally dehydrated onions were always next. The strange thumb-controlled funnel thingy that deposited exactly the right amount of ketchup was always in exactly in the same place, in it’s holder, on the end of the counter. The mustard funnel thingy was always to its right. At least that’s the way they did it back in the eighties.